Is Inflation a Tax? In this article we explore the concept of the inflation tax and lay out why inflation is unjust and puts your money at risk.

Inflation has long been a subject of economic discussions, often intertwined with debates about government policies and their impact on citizens’ wallets.

The question of whether inflation can be likened to a tax is a matter of contention, yet a closer examination of the mechanics behind inflation and its implications on the economy and individuals’ financial well-being sheds light on the notion that inflation is indeed a form of taxation, albeit one that operates in a unique and indirect manner.

Table of Contents

The Government’s Revenue Streams

To comprehend whether inflation operates is tax, it’s essential to delve into how governments obtain the funds necessary for their expenditures. Governments have three primary avenues through which they acquire money: taxation, borrowing, and printing money.

While taxation is a familiar concept to most, borrowing and money printing are equally integral components of government financing. Taxation involves levying charges on individuals and businesses based on income, consumption, ownership, and other activities. It’s a straightforward process through which governments directly collect funds from citizens.

Borrowing, on the other hand, entails the issuance of bonds, with buyers lending money to the government in exchange for the promise of future repayment with interest. Lastly, governments can resort to money printing, a process facilitated by central banks. In this scenario, the central bank buys government bonds using newly created money, injecting it into the economy.

Inflation Tax as a Monetary Phenomenon

The connection between inflation and taxation becomes apparent when examining the relationship between money creation and price inflation.

The principle that governs this relationship is often summarized by the phrase “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” as articulated by renowned economist Milton Friedman. When the money supply increases, the prices of goods and services tend to rise due to the abundance of money in circulation.

The process of money creation involves the central bank purchasing government bonds from private institutions using newly printed money. This money eventually flows into the economy, leading to increased spending and demand for goods and services. As demand surges, prices rise, eroding the purchasing power of the currency. This inflation effectively acts as a hidden tax, as it diminishes the value of the money held by individuals and reduces their ability to buy the same amount of goods and services with their savings.

The Relationship Between Inflation and Government Debt

Inflation also plays a role in government debt dynamics. When inflation rates rise, the real cost of debt decreases for the government. This occurs because the nominal value of the debt remains constant, while the real value diminishes in an inflationary environment. As a result, the government benefits from reduced debt burdens, effectively transferring wealth from savers to itself. This dynamic further supports the notion that inflation can be considered a form of taxation, as it redistributes wealth from citizens to the government through the erosion of purchasing power.

The Cantillon Effect and Special Interest Influence

The Cantillon effect highlights another dimension of how inflation operates as a form of taxation. This effect posits that those who receive newly created money first, such as large financial institutions like banks, benefit the most. They acquire the money before it causes general price increases, essentially gaining purchasing power. In contrast, the costs of inflation are borne by a dispersed and unorganized group of individuals who hold the currency.

This disparity in impact aligns with economist Mancur Olson’s logic of collective action. The beneficiaries of money creation, due to their concentrated interests and resources, are more likely to influence central bank policies to their advantage. Meanwhile, the costs, spread across a larger and less organized group, result in less concerted efforts to oppose such policies. This imbalance further supports the idea that inflation is, in essence, a tax that favors certain interest groups at the expense of the broader population.

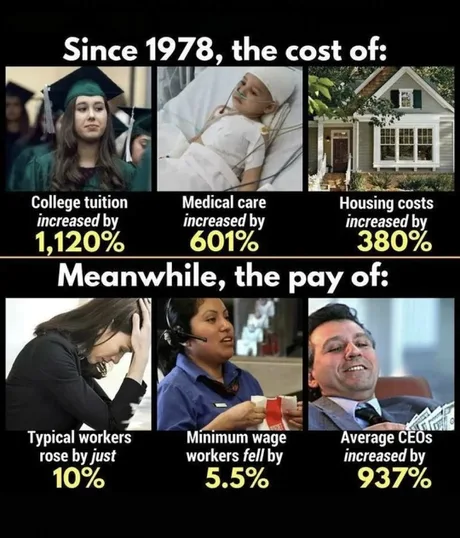

Inflation’s Real-World Impact – Is inflation a tax?

Recent economic indicators highlight the tangible impact of inflation on individuals’ lives. Rising prices, as measured by metrics like the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index, directly translate to increased costs for households. The average American family is projected to incur an additional $5,200 in expenses to maintain their previous standard of living due to inflation. This real-world consequence underscores the argument that inflation operates as a tax on citizens’ purchasing power.

Is inflation a tax? Yes!

Inflation, often referred to as an abstract economic force, can indeed be conceptualized as a form of taxation.

The mechanisms by which governments create money, influence price levels, and affect the value of citizens’ savings collectively resemble a hidden tax.

The interaction between money creation, price inflation, and government debt dynamics supports the idea that inflation erodes individuals’ purchasing power and redistributes wealth to the government.

Furthermore, the Cantillon effect and the influence of special interest groups underscore the unequal impact of inflation on various segments of society.

As such, while inflation might not fit the traditional definition of a tax, its implications on citizens’ financial well-being and its parallel mechanisms with taxation suggest that inflation can be perceived as a unique form of taxation – an “inflation tax” – with consequences that extend beyond economic theory and into the lives of everyday people.

Below is a table that demonstrates the impact of inflation compounded over five decades on an annual wage of $36,000, using inflation rates of 2%, 5%, 10%, and 15%:

| Year | 2% Inflation | 5% Inflation | 10% Inflation | 15% Inflation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | $36,000.00 | $36,000.00 | $36,000.00 | $36,000.00 |

| 10 | $24,494.39 | $17,297.63 | $11,603.22 | $7,797.04 |

| 20 | $16,670.51 | $8,424.30 | $3,743.16 | $1,662.46 |

| 30 | $11,357.53 | $3,796.74 | $1,228.02 | $398.28 |

| 40 | $7,744.31 | $1,295.78 | $163.05 | $20.51 |

| 50 | $5,278.98 | $241.56 | $4.78 | $0.09 |

This table underscores how different inflation rates can substantially impact the real value of an annual wage of $36,000 over a period of five decades. Higher inflation rates erode the purchasing power of money more rapidly, leading to reduced affordability of goods and services over time. It highlights the importance of considering inflation when planning for long-term financial goals and retirement.