We already discussed whether inflation is taxation in another article. Today, we will take a closer look at the inflation tax from an “austrian” perspective.

Introduction: The Austrian School

In the realm of economics, the concept of taxation typically evokes images of individuals and businesses paying a portion of their income to fund government operations and services.

However, there exists a subtler form of taxation—one that often goes unnoticed but wields significant impact: inflation.

This notion is particularly resonant within the framework of the Austrian School of Economics, which offers valuable insights into the relationship between inflation and taxation.

The Austrian School of Economics, renowned for its emphasis on individual decision-making, spontaneous order, and the importance of market forces, provides a unique lens through which to analyze the notion of inflation as a form of taxation.

Inflation Tax Explained

Imagine you have a jar of your favorite candy. Every time you want to buy something, you use a few candies to pay for it.

Now, what if someone started adding more candies to that jar every day? At first, it might seem great because you have more candies to spend.

But here’s the catch: when everyone else also gets more candies, the price of things you want to buy starts to go up.

Inflation is like a sneaky tax that doesn’t involve the government taking money directly from you. Instead, it’s about the value of your money decreasing over time. Let’s break it down.

Governments need money to run their programs, just like you need money to buy things. They have a few ways to get it:

- Taxation: You pay taxes on your income, purchases, and other activities. This money goes into government funds.

- Borrowing: Governments can borrow money by selling something called bonds. People buy these bonds, and the government promises to pay them back with extra money later on.

- Printing Money: This is where things get interesting. Governments can create new money out of thin air. They don’t print physical bills every time; it’s more like adding digital money to the system. The money they earn from minting money (inflation) is also called seigniorage.

Now, here’s the twist: when there’s more money around, prices tend to go up. If everyone suddenly had twice as much money, sellers might start charging more for their products because they know people have more to spend. This increase in prices is called inflation and you could say it’s an inflation tax.

So, how is inflation like a tax? Think of it this way: you work hard to earn money and save it up. But if the value of money is going down because of inflation, your savings can’t buy as much as they used to. It’s like you’re losing a little bit of your money’s worth without even realizing it. This decrease in purchasing power is what makes inflation feel like a tax on your savings.

Now, let’s link this to the Austrian School of Economics. They emphasize how governments creating extra money can lead to problems.

When new money is made, it usually doesn’t affect everyone at the same time. Big banks and influential groups often get their hands on the new money first.

They benefit from having more money before prices rise due to inflation. This uneven distribution of benefits is a bit like special treatment.

The rest of us, who don’t get the new money right away, end up paying the price through higher prices for things we need. This uneven impact is similar to a hidden tax.. It’s not as obvious as the regular taxes you see on your paycheck, but it still affects your financial well-being. Therefore many call it what it is: inflation tax.

The Austrian School’s perspective suggests that this inflation-driven decrease in your money’s value is a form of government intervention.

Even though they’re not directly taking money from your pocket, they’re reducing the value of what you have. This can hurt those who don’t have the power or resources to protect themselves from the effects of inflation.

In a nutshell, inflation tax might not feel like a traditional tax, but it does eat away at your savings and purchasing power.

The Austrian School’s viewpoint helps us understand how the government’s actions, like printing more money, can indirectly affect our finances. It’s a reminder that even seemingly small changes in the economy can have big consequences for our wallets.

Inflation Explained

At its core, inflation refers to the sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy.

While inflation is often attributed to a variety of factors, the Austrian School shines a spotlight on the role of money supply growth—a crucial perspective when considering whether inflation can indeed be viewed as a form of taxation.

Inflation, in its essence, can be seen as a result of monetary policies that increase the money supply. Governments, constrained by the need to fund public expenditures, have various means at their disposal, including taxation, borrowing, and the printing of money.

The Argument for Inflation

The Austrian School contends that the act of printing money, or increasing the money supply through mechanisms like quantitative easing, is tantamount to creating new currency out of thin air. This newly created money enters the economy and, over time, dilutes the value of the existing currency, leading to a decrease in purchasing power.

To understand how this process aligns with the idea of taxation, it’s crucial to recognize the interconnectedness of inflation and the diminishing value of money.

Inflation Tax – Are you affected?

Just as a traditional tax takes a portion of an individual’s income, the erosion of purchasing power caused by inflation effectively reduces the value of every unit of currency held by individuals and businesses.

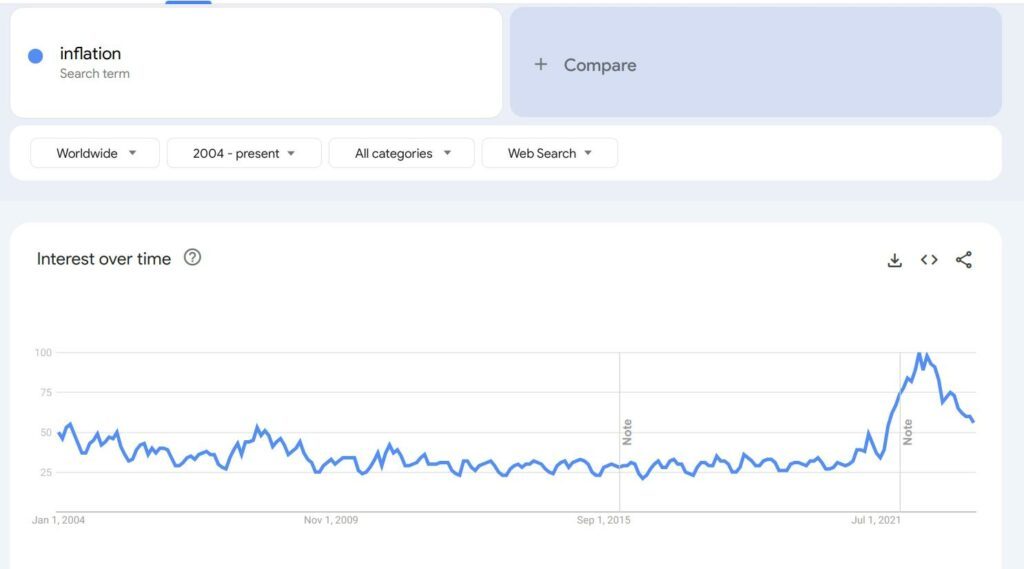

Inflation is a global problem because all governments print money. Google Trends data reveals how this problem is becoming more serious in recent years.

In this sense, while not overtly confiscatory like traditional taxation, inflation chips away at the real value of people’s savings, earnings, and investments—an outcome strikingly similar to the effects of taxation.

Moreover, the Austrian School’s perspective on inflation highlights the mechanism through which this subtle form of taxation can disproportionately affect different segments of the population.

The process of money creation is often accompanied by a “Cantillon effect,” where the first recipients of the newly created money, typically financial institutions and well-connected entities, benefit from the increased purchasing power before inflation takes its toll.

This concentration of initial benefits among a select group can be likened to special interests gaining an advantage from government policies that go unnoticed by the broader population.

This disparity between those who benefit initially and the larger populace that bears the brunt of inflation aligns with the Austrian School’s insights into the dynamics of collective action and concentrated benefits.

The concept of “logic of collective action,” as posited by economist Mancur Olson, holds that smaller, organized groups tend to have more influence over policies than larger, dispersed groups.

In the case of inflation, while the costs are borne by the public at large, the initial beneficiaries of the newly created money have a vested interest in maintaining policies that perpetuate inflation.

In the context of the Austrian School’s framework, the question of whether inflation can be considered a form of taxation is nuanced.

While inflation does not adhere to the conventional understanding of taxation—where explicit funds are collected by the government—it does align with the Austrian perspective of government interventions that result in the redistribution of wealth and resources.

In this light, inflation can be seen as a mechanism through which the government indirectly extracts value from its citizens’ wealth and savings, much like a stealthy tax that erodes purchasing power over time. Or in other words: the inflation tax.

Schlussfolgerung

In conclusion, the Austrian School of Economics provides a compelling vantage point from which to explore the relationship between inflation and taxation.

For most followers of Austrian thought, the inflation tax is clearly an unethical instrument of wealth redistribution.

By focusing on the impact of money supply growth and its consequences, the Austrian perspective sheds light on the ways in which inflation can be viewed as a subtle and indirect form of taxation.

While inflation tax might not fit the traditional definition of taxation, its effects on the value of money, wealth distribution, and special interest influence align closely with the Austrian School’s emphasis on market forces, individual decision-making, and unintended consequences.

Thus, as we contemplate the intricacies of economic policies, it is essential to consider the Austrian School’s insights when evaluating the implications of inflation as a form of taxation.